The late Joan Didion said, “I don’t know what I think until I write it down.” The following is Vino doing just that.

I dated a 39-year-old man who compared a past girlfriend crying to getting a hair in his food. “Sometimes you’re so into it you keep eating, sometimes you send it back,” he told me. I was too distracted by the idea of him eating something with a hair in it to see that this was a bad sign.

When he ended things two and a half months in, I cried so much it was like serving him up a whole plate of pubes. He needed to be alone. He thought he was ready for a relationship but wasn’t. It wasn’t me, it was him. He rattled off these platitudes with a twinge of affection that made the surgical breakup sting.

We’d dated for ten weeks. That’s it. I was embarrassed that I had such an emotional response to a short-term relationship. But after being single for the better part of a decade, the difference between the heartbreak of losing love and the dull, aching pain of getting it wrong again was almost indiscernible. The sadness of feeling like a discarded menu item, knowing I’ve sent many back myself. He moved too fast. We didn’t have enough in common. It wasn’t him, it was me.

I have only had one serious relationship between the ages of 26 and 30, and it was not exactly built on a healthy foundation. It does not take a therapist to point out that it is probably not a coincidence that I have failed to get past the first few months of dating with almost anyone since. And then it happened again. Another smell on my pillow to launder. Another set of inside jokes to forget.

What I was really wrestling with was an emotion that poet and essayist Amy Key described as “lovelessness,” or what Merriam-Webster defines as a sense of being “not loved” or “having no love.” To Key, lovelessness is essentially the sneaking suspicion that our person may not exist, a reality she faces in her book Arrangements in Blue: Notes on Loving and Living Alone. The book is inspired by Joni Mitchell’s album, “Blue,” which was recorded in the wake of her breakup with Graham Nash and rebound with James Taylor. Key’s prose is not about the ups and downs of romantic love but what’s left when a partner never shows up. Or, as she puts it in her dedication, “This book is for anyone who needs a love story of being alone.”

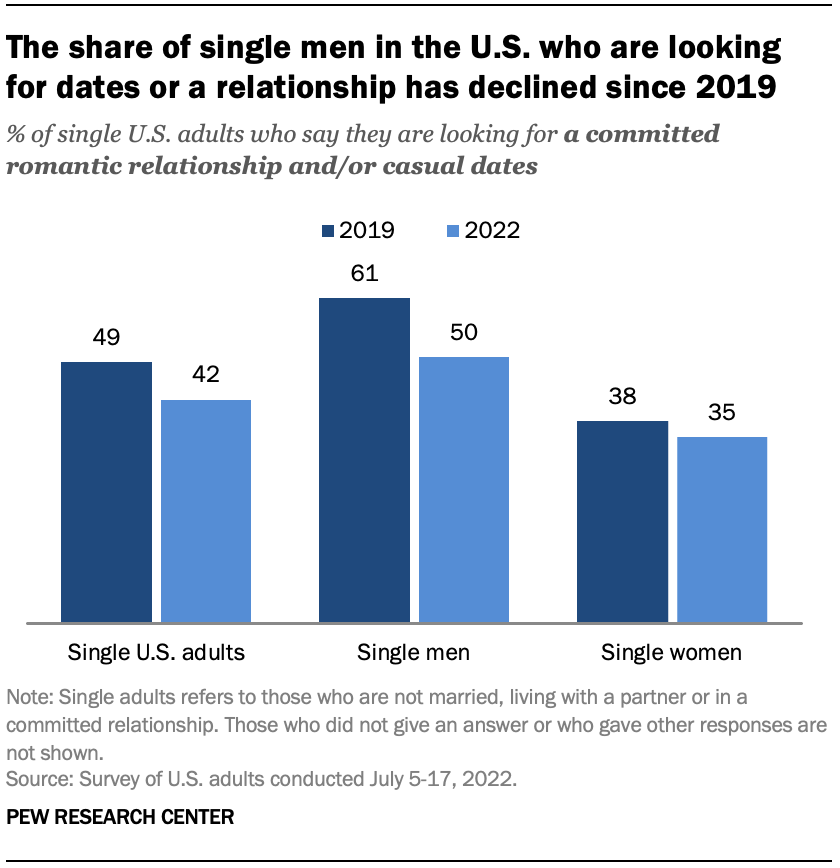

Judging by the research, this dedication implicitly includes more people than ever. Love escapes 35 percent of single adults who have never been in a romantic relationship. The drop-off from romantic relationships appears to be steeper for men under 30, 63% of which report being single. Additional data indicates that one of the main reasons young adults specifically aren’t having sex is because they aren’t coupling up like they used to. Enough people have given up on love that it has spawned an entire incel subculture.

At the same time, there are more resources than ever on how to get into a relationship. This drought of romantic relationships enriched an industry of coaches, influencers, and self-help authors. Platforms like TikTok and Instagram have popularized concepts like Attachment Theory and love languages. We have intellectualized and optimized as much as possible around romantic relationships but still cannot figure out love.

@therapyjeff Why you have the attachment style you have. @doodledwellness_ #anxiousattachment #therapy #avoidantattachment ♬ original sound – TherapyJeff

We’ve mostly gotten better at discussing why we are failing. The disconnection brought on by smartphones and the dating app-induced illusion that we have nearly infinite options has shouldered most of the blame. Throw in the isolation of the pandemic that kicked off this decade. It makes sense that we would end up exchanging tasteful nudes with strangers and sleep by ourselves instead.

Clinical psychologist Carla Manly acknowledged, “Meeting a good match organically is far more difficult than it used to be.” More people are working from home, buying groceries online, and Amazoning everything else. With fewer opportunities to interact with the outside world comes fewer opportunities to meet people. The bigger issue is how single people have responded to this, often looking inward for answers and ways to blame ourselves. “This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy that can lead to deep loneliness,” Manly, the author of the self-help book Date Smart, explained.

Dating apps offer an overstated promise of solving this problem by casting a wider net. In my personal experience, this leads to more of a mutual scavenger hunt for things in common that rarely amounts to true intimacy. Most of the time, the short-lived connection is based on the shared suspicion that we were never supposed to be in each other’s lives.

Still, people continue to defy the odds. They fall in love on Tinder or slide into their future spouses’ DMs on Instagram. That is why I cannot blame technology entirely. These fundamental aspects of modern culture are obvious variables, making them easy to dissect. That said, human beings are built to adapt, and the notion that we would be unable to work around the obstacles seemed like an oversimplification.

When I spoke to sociologist Sarah Adeyinka-Skold, who has studied inequities in the dating world, she offered a different theory. This problem of lovelessness has always existed, but it disproportionately affected already marginalized groups. “Black women have been feeling this for at least 10 to 15 years,” she told me. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, rates of unmarried are higher among Black individuals and significantly higher for Black women.

What has changed over the past 15 years is that the struggle to find and maintain romantic relationships has started to impact more privileged groups. “This is simply the pattern in the U.S.,” Adeyinka-Skold explained, comparing it to the war on drugs. When black families were dealing with loved ones in the throes of crack addiction in the 1980s, they were never given the benefit of the doubt. However, once the opiate epidemic reached white people, addiction started to be taken seriously as a systemic mental health issue.

In any society that’s stratified by race, class, or gender, “the folks that are at the bottom of that hierarchy are going to experience the shocks of the system first,” she said, But when lovelessness starts happening to those further up, “suddenly it feels like a new problem, but it’s not. We just didn’t pay attention to the people who it was happening to first.”

The reality is that when systems fail to meet people’s basic needs, it’s reasonable to expect those individuals to struggle with relationships. Issues like economic insecurity, a decline in home ownership, and eroding access to healthcare are trickling up the hierarchy. We are all craving stability, and then eating lunch that was delivered while we work to afford that $40 sandwich we ordered. Living has become harder for everyone. And yet, we continue to be surprised that the same is true for loving.

Look at it this way: do you really think your therapy-averse parents’ generation was better at relationships than you are? What is more likely is that because Baby Boomers came of age during a time of economic prosperity and had the support of affordable housing and higher education, they could care for another person without putting their survival first. That’s not to say that love is impossible now, but the undercurrents that keep us from each other are gaining strength. That’s why we cling to phones and apps like deflating rafts but ultimately feel like we are drowning out there.

I didn’t realize how much this sociologist’s words stuck with me until months later. I was venting to my old college friend Steph about how hard it was to meet someone.

“I don’t have advice. All I know is that if I never met my wife, I would be as lost as everyone else,” she said. On the surface, this could have been taken as the standard, “You just haven’t met the right person.” But this was different.

It could very well be a coincidence that Steph is not straight or white, but there was a lack of entitlement to love that I had not encountered dating — an entitlement that I had not clocked in myself before speaking to Adeyinka-Skold.

Steph didn’t treat love like a meal she was deciding to send back or not. Her love was more like a casino than a restaurant, where the risks are ample, and you’re guaranteed nothing but dopamine (and maybe a free drink). It’s not that we’re doomed to lose, but the house does not care if you like to gamble. And if you cannot appreciate the luck involved in the process, the unforgiving fluorescent lighting makes the exit easy to find.

Looking at it in terms of odds, there has never been a more thrilling time to tolerate such risk. It had to be easier to stomach than hair in my food.